goroutine和channel是go语言的两大基石,这边主要来研究一下channel,goroutine可以查看这里。

channel核心设计思想:不是通过共享内存来通信,而是通过通信来共享内存。

基本概念

声明

var ch chan int

var m map[ string] chan bool

ch := make(chan int)

c := make(chan int, 1024)--带缓冲的channel,后面的参数是缓冲大小

c := make([]chan int, 1024)--这个是是数组

单向channel

var ch1 chan int // ch1是一个正常的 channel,不是单向的

var ch2 chan<- float64// ch2是单向channel,只用于写float64数据

var ch3 <-chan int // ch3 是单向channel,只用于读取int数据

ch4 := make( chan int)

ch5 := <-chan int(ch4) // ch5就是一个单向的读取channel

ch6 := chan<- int(ch4) // ch6 是一个单向的写入channel

读写

写 ch <- 1 向channel写入数据通常会导致程序阻塞,直到有其他goroutine从这个channel中读取数据

读 value := <-ch 如果channel之前没有写入数据,那么从channel中读取数据也会导致程序阻塞,直到channel中被写入数据为止——这两点可以用于数据同步。

关闭

关闭close()----x, ok := <-ch,可以通过ok来判断channel是否关闭,一个非空的通道也是可以关闭的,但是通道中剩下的值仍然可以被接收到。

ok的结果和含义:

- `true`:读到通道数据,不确定是否关闭,可能channel还有保存的数据,但channel已关闭。

- `false`:通道关闭,无数据读到。

- 读已经关闭的 chan 能一直读到东西,但是读到的内容根据通道内关闭前是否有元素而不同。

- 如果 chan 关闭前,buffer 内有元素还未读 , 会正确读到 chan 内的值,且返回的第二个 bool 值(是否读成功)为 true。

- 如果 chan 关闭前,buffer 内有元素已经被读完,chan 内无值,接下来所有接收的值都会非阻塞直接成功,返回 channel 元素的零值,但是第二个 bool 值一直为 false。

- 写已经关闭的 chan 会 panic

实例

package main

import (

"fmt"

)

func producer(chnl chan int) {

for i := 0; i < 10; i++ {

chnl <- i

}

close(chnl)

}

func main() {

ch := make(chan int)

go producer(ch)

for {

v, ok := <-ch

if ok == false {

break

}

fmt.Println("Received ", v, ok)

}

}

实现原理

具体实现

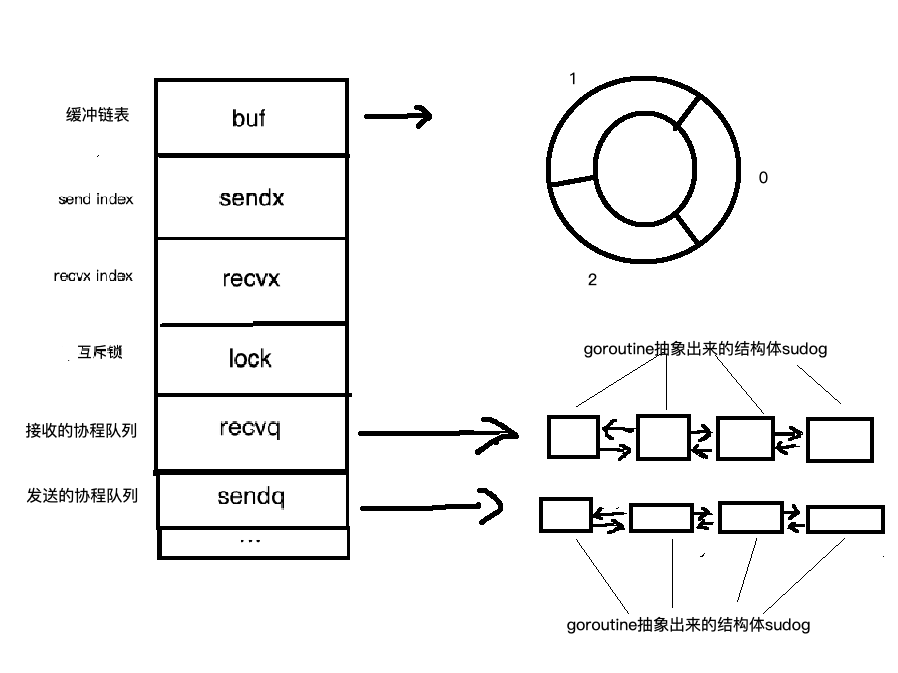

源码位于/runtime/chan.go中(目前版本:1.11)。结构体为hchan。

type hchan struct {

qcount uint // total data in the queue

dataqsiz uint // size of the circular queue

buf unsafe.Pointer // points to an array of dataqsiz elements

elemsize uint16

closed uint32

elemtype *_type // element type

sendx uint // send index

recvx uint // receive index

recvq waitq // list of recv waiters

sendq waitq // list of send waiters

// lock protects all fields in hchan, as well as several

// fields in sudogs blocked on this channel.

//

// Do not change another G's status while holding this lock

// (in particular, do not ready a G), as this can deadlock

// with stack shrinking.

lock mutex

}

详细说明

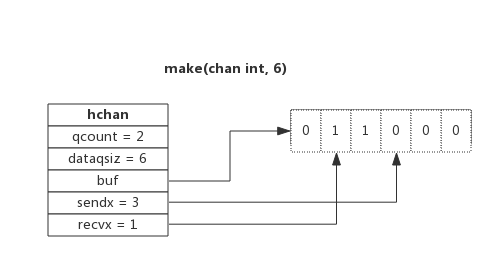

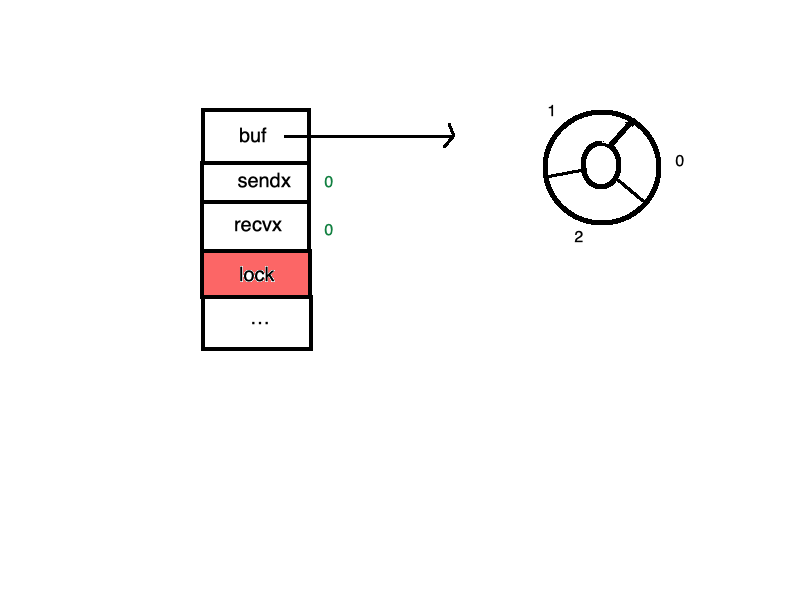

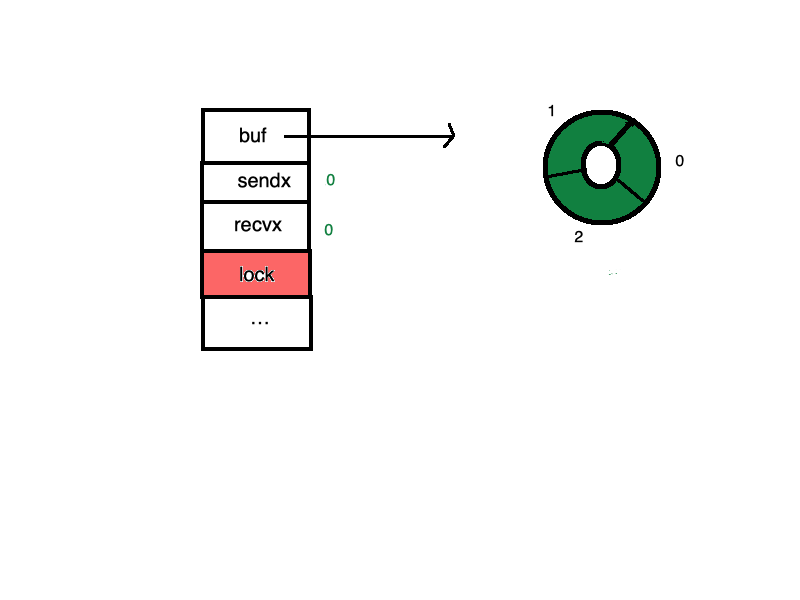

环形队列

chan内部实现了一个环形队列作为其缓冲区,队列的长度是创建chan时指定的。

下图展示了一个可缓存6个元素的channel示意图:

- dataqsiz指示了队列长度为6,即可缓存6个元素;

- buf指向队列的内存,队列是一个环形队列,队列中还剩余两个元素;

- qcount表示队列中还有两个元素;

- sendx指示后续写入的数据存储的位置,取值[0, 6);

- recvx指示从该位置读取数据, 取值[0, 6);

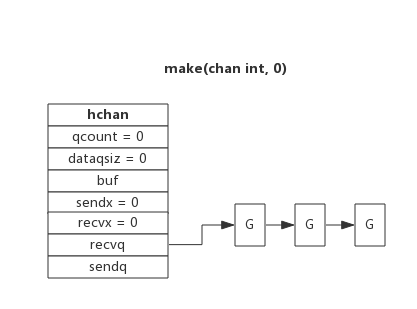

等待队列

recvq和sendq分别是接收(<-channel)或者发送(channel <- xxx)的goroutine抽象出来的结构体(sudog)的队列。是个双向链表

从channel读数据,如果channel缓冲区为空或者没有缓冲区,当前goroutine会被阻塞。

向channel写数据,如果channel缓冲区已满或者没有缓冲区,当前goroutine会被阻塞。

被阻塞的goroutine将会挂在channel的等待队列中:

因读阻塞的goroutine会被向channel写入数据的goroutine唤醒; 因写阻塞的goroutine会被从channel读数据的goroutine唤醒;下图展示了一个没有缓冲区的channel,有几个goroutine阻塞等待读数据:

注意,一般情况下recvq和sendq至少有一个为空。只有一个例外,那就是同一个goroutine使用select语句向channel一边写数据,一边读数据。

类型信息

一个channel只能传递一种类型的值,类型信息存储在hchan数据结构中。

elemtype代表类型,用于数据传递过程中的赋值; elemsize代表类型大小,用于在buf中定位元素位置。锁

一个channel同时仅允许被一个goroutine读写,为简单起见,本章后续部分说明读写过程时不再涉及加锁和解锁。

实现流程

下面我们来详细介绍hchan中各部分是如何使用的。

先从创建开始

我们首先创建一个channel。

ch := make(chan int, 3)

创建channel实际上就是在内存中实例化了一个hchan的结构体,并返回一个ch指针,我们使用过程中channel在函数之间的传递都是用的这个指针,这就是为什么函数传递中无需使用channel的指针,而直接用channel就行了,因为channel本身就是一个指针。

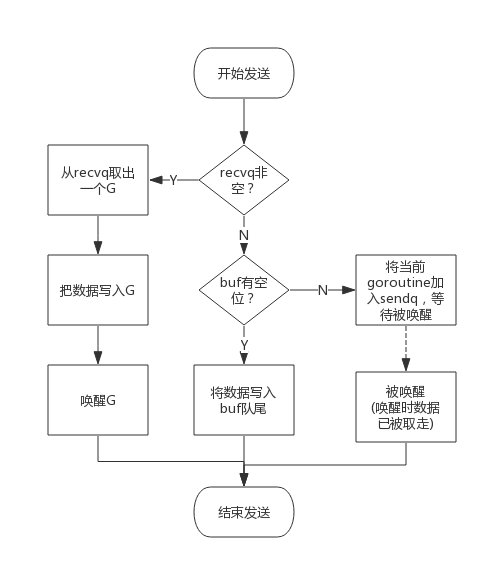

向channel写数据

向一个channel中写数据简单过程如下:

- 如果等待接收队列recvq不为空,说明缓冲区中没有数据或者没有缓冲区,此时直接从recvq取出G,并把数据写入,最后把该G唤醒,结束发送过程;

- 如果缓冲区中有空余位置,将数据写入缓冲区,结束发送过程;

- 如果缓冲区中没有空余位置,将待发送数据写入G,将当前G加入sendq,进入睡眠,等待被读goroutine唤醒;

简单流程图如下:

数据写入buf

- 第一,加锁

- 第二,把数据从goroutine中copy到“队列”中(或者从队列中copy到goroutine中)。

- 第三,释放锁

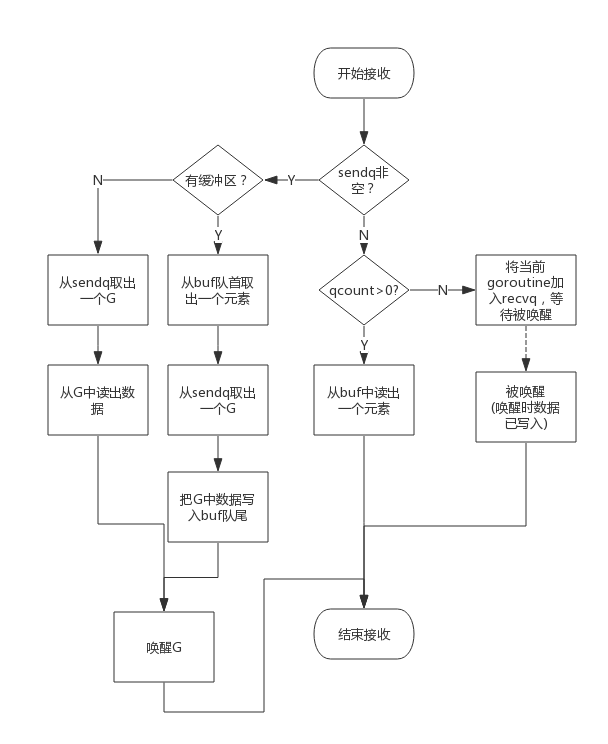

从channel读数据

从一个channel读数据简单过程如下:

- 如果等待发送队列sendq不为空,且没有缓冲区,直接从sendq中取出G,把G中数据读出,最后把G唤醒,结束读取过程;

- 如果等待发送队列sendq不为空,此时说明缓冲区已满,从缓冲区中首部读出数据,把G中数据写入缓冲区尾部,把G唤醒,结束读取过程;

- 如果缓冲区中有数据,则从缓冲区取出数据,结束读取过程;

- 将当前goroutine加入recvq,进入睡眠,等待被写goroutine唤醒;

简单流程图如下:

数据读取buf

- 第一,加锁

- 第二,把数据从goroutine中copy到“队列”中(或者从队列中copy到goroutine中)。

- 第三,释放锁

至于为什么channel会使用循环链表作为缓存结构,我个人认为是在缓存列表在动态的send和recv过程中,定位当前send或者recvx的位置、选择send的和recvx的位置比较方便吧,只要顺着链表顺序一直旋转操作就好。

关闭channel

关闭channel时会把recvq中的G全部唤醒,本该写入G的数据位置为nil。把sendq中的G全部唤醒,但这些G会panic。

除此之外,panic出现的常见场景还有:

- 关闭值为nil的channel

- 关闭已经被关闭的channel

- 向已经关闭的channel写数据

使用

在prometheus中的使用

// Describe simply sends the two Descs in the struct to the channel.

func (e *exporter) Describe(ch chan<- *prometheus.Desc) {

metricCh := make(chan prometheus.Metric)

doneCh := make(chan struct{})

go func() {

for m := range metricCh {

ch <- m.Desc()

}

close(doneCh)

}()

e.Collect(metricCh)

close(metricCh)

<-doneCh

}

range取数据阻塞,等待数据传入channel

donech防止程序结束,类似于控制并发等待的效果。

阻塞

发送与接收默认是阻塞的。这是什么意思?当把数据发送到信道时,程序控制会在发送数据的语句处发生阻塞,直到有其它 Go 协程从信道读取到数据,才会解除阻塞。与此类似,当读取信道的数据时,如果没有其它的协程把数据写入到这个信道,那么读取过程就会一直阻塞着。

信道的这种特性能够帮助 Go 协程之间进行高效的通信,不需要用到其他编程语言常见的显式锁或条件变量。

package main

import (

"fmt"

)

func hello(done chan bool) {

fmt.Println("Hello world goroutine")

done <- true

}

func main() {

done := make(chan bool)

go hello(done)

<-done

fmt.Println("main function")

}

在上述程序里,我们在第 12 行创建了一个 bool 类型的信道 done,并把 done 作为参数传递给了 hello 协程。在第 14 行,我们通过信道 done 接收数据。这一行代码发生了阻塞,除非有协程向 done 写入数据,否则程序不会跳到下一行代码。于是,这就不需要用以前的 time.Sleep 来阻止 Go 主协程退出了。

死锁

使用信道需要考虑的一个重点是死锁。当 Go 协程给一个信道发送数据时,照理说会有其他 Go 协程来接收数据。如果没有的话,程序就会在运行时触发 panic,形成死锁。

有写无读(正常需要两个goroutine)

同理,当有 Go 协程等着从一个信道接收数据时,我们期望其他的 Go 协程会向该信道写入数据,要不然程序就会触发 panic。

package main

func main() {

var ch = make(chan int)

ch <- 1

println(<-ch)

}

运行打印结果为:

fatal error: all goroutines are asleep - deadlock!

goroutine 1 [chan send]:

main.main()

/tmp/sandbox117018544/main.go:5 +0x60

死锁了,为什么会这样呢,因为ch是一个无缓冲的channel,在执行到ch <- 1就阻塞了当前goroutine(也就是main函数所在的goroutine),后面打印语句根本没机会执行

稍加修改即能正常运行

package main

func main() {

var ch = make(chan int)

go func() {

ch <- 1

println("sender")

}()

println(<-ch)

}

因为此时ch既有发送也有接收而且不在同一个goroutine里面,此时它们不会相互阻塞.

package main

import (

"fmt"

)

func main() {

ch := make(chan string, 2)

ch <- "naveen"

ch <- "paul"

ch <- "steve"

fmt.Println(<-ch)

fmt.Println(<-ch)

}

上面的程序,我们想向容量为2的channel中写入3个字符串。程序执行到11行时候将会被阻塞,因为此时channel缓冲区已经满了。如果没有其他goroutine从中读取数据,程序将会死锁。报错如下:

fatal error: all goroutines are asleep - deadlock!

goroutine 1 [chan send]:

main.main()

/tmp/sandbox274756028/main.go:11 +0x100

相互读,相互等待的死锁

通道1中调用了通道2,通道2中调用通道1

func main() {

c1,c2:=make(chan int),make(chan int)

go func() {

for {

select{

case <-c1:

c2<-10

}

}

}()

for {

select{

case <-c2:

c1<-10

}

}

}

大体正常就是这两种情况,但是死锁的出现的情况很多,但都不外乎是争抢资源和数据通信引起。

select的使用

在执行select语句的时候,运行时系统会自上而下地判断每个case中的发送或接收操作是否可以被立即执行(立即执行:意思是当前Goroutine不会因此操作而被阻塞)

在 select 中使用发送操作并且有 default可以确保发送不被阻塞!如果没有 case,select 就会一直阻塞。

为了便于理解,我们首先给出一个代码片段:

// https://talks.golang.org/2012/concurrency.slide#32

select {

case v1 := <-c1:

fmt.Printf("received %v from c1\n", v1)

case v2 := <-c2:

fmt.Printf("received %v from c2\n", v1)

case c3 <- 23:

fmt.Printf("sent %v to c3\n", 23)

default:

fmt.Printf("no one was ready to communicate\n")

}

上面这段代码中,select 语句有四个 case 子语句,前两个是 receive 操作,很好理解就是channel中没有数据的时候一直等待,直到有数据直接读出来赋值,第三个是 send 操作,这个其实也是用的channel的阻塞,往channel中写数据,channel要有缓存才能写进去,满了就会一直阻塞,最后一个是默认操作。代码执行到 select 时,case 语句会按照源代码的顺序被评估,且只评估一次,评估的结果会出现下面这几种情况:

除 default 外,如果只有一个 case 语句评估通过,那么就执行这个case里的语句;

除 default 外,如果有多个 case 语句评估通过,那么通过伪随机的方式随机选一个;

如果 default 外的 case 语句都没有通过评估,那么执行 default 里的语句;

如果没有 default,那么 代码块会被阻塞,直到有一个 case 通过评估;否则一直阻塞,所以select是很实用的方式,我们在很多地方都使用:

GO select用法详解

golang 的 select 就是监听 IO 操作,当 IO 操作发生时,触发相应的动作。

在执行select语句的时候,运行时系统会自上而下地判断每个case中的发送或接收操作是否可以被立即执行(立即执行:意思是当前Goroutine不会因此操作而被阻塞)

select的用法与switch非常类似,由select开始一个新的选择块,每个选择条件由case语句来描述。与switch语句可以选择任何可使用相等比较的条件相比,select有比较多的限制,其中最大的一条限制就是每个case语句里必须是一个IO操作,确切的说,应该是一个面向channel的IO操作。

下面这段话来自官方文档:

A "select" statement chooses which of a set of possible send or receive operations will proceed. It looks similar to a "switch" statement but with the cases all referring to communication operations.

语法格式如下:

select {

case SendStmt:

//statements

case RecvStmt:

//statements

default:

//statements

}

其中,

SendStmt : channelVariable <- value

RecvStmt : variable <-channelVariable

A case with a RecvStmt may assign the result of a RecvExpr to one or two variables, which may be declared using a short variable declaration(IdentifierList := value). The RecvExpr must be a (possibly parenthesized) receive operation(<-channelVariable). There can be at most one default case and it may appear anywhere in the list of cases.

示例:

ch1 := make(chan int, 1)

ch2 := make(chan int, 1)

ch1 <- 1

select {

case e1 := <-ch1:

//如果ch1通道成功读取数据,则执行该case处理语句

fmt.Printf("1th case is selected. e1=%v", e1)

case e2 := <-ch2:

//如果ch2通道成功读取数据,则执行该case处理语句

fmt.Printf("2th case is selected. e2=%v", e2)

default:

//如果上面case都没有成功,则进入default处理流程

fmt.Println("default!.")

}

超时机制也可以使用上面的方式用select来实现。

Execution of a “select” statement proceeds in several steps:

1、For all the cases in the statement, the channel operands of receive operations and the channel and right-hand-side expressions of send statements are evaluated exactly once, in source order, upon entering the "select" statement.(所有channel表达式都会被求值、所有被发送的表达式都会被求值。求值顺序:自上而下、从左到右)

2、If one or more of the communications can proceed, a single one that can proceed is chosen via a uniform pseudo-random selection. Otherwise, if there is a default case, that case is chosen. If there is no default case, the "select" statement blocks until at least one of the communications can proceed.(如果有一个或多个IO操作可以完成,则Go运行时系统会随机的选择一个执行,否则的话,如果有default分支,则执行default分支语句,如果连default都没有,则select语句会一直阻塞,直到至少有一个IO操作可以进行)

3、Unless the selected case is the default case, the respective communication operation is executed.

4、If the selected case is a RecvStmt with a short variable declaration or an assignment, the left-hand side expressions are evaluated and the received value (or values) are assigned.

5、The statement list of the selected case is executed.

示例1:select语句会一直等待,直到某个case里的IO操作可以进行

//main.go

package main

import "fmt"

import "time"

func f1(ch chan int) {

time.Sleep(time.Second * 5)

ch <- 1

}

func f2(ch chan int) {

time.Sleep(time.Second * 10)

ch <- 1

}

func main() {

var ch1 = make(chan int)

var ch2 = make(chan int)

go f1(ch1)

go f2(ch2)

select {

case <-ch1:

fmt.Println("The first case is selected.")

case <-ch2:

fmt.Println("The second case is selected.")

}

}

编译运行:

C:/go/bin/go.exe run test14.go [E:/project/go/proj/src/test]

The first case is selected.

成功: 进程退出代码 0.

示例2:所有跟在case关键字右边的发送语句或接收语句中的通道表达式和元素表达式都会先被求值。无论它们所在的case是否有可能被选择都会这样。

求值顺序:自上而下、从左到右

此示例使用空值channel进行验证。

//main.go

package main

import (

"fmt"

)

//定义几个变量,其中chs和numbers分别代表通道列表和整数列表

var ch1 chan int

var ch2 chan int

var chs = []chan int{ch1, ch2}

var numbers = []int{1, 2, 3, 4, 5}

func main() {

select {

case getChan(0) <- getNumber(2):

fmt.Println("1th case is selected.")

case getChan(1) <- getNumber(3):

fmt.Println("2th case is selected.")

default:

fmt.Println("default!.")

}

}

func getNumber(i int) int {

fmt.Printf("numbers[%d]\n", i)

return numbers[i]

}

func getChan(i int) chan int {

fmt.Printf("chs[%d]\n", i)

return chs[i]

}

编译运行:

C:/go/bin/go.exe run test4.go [E:/project/go/proj/src/test]

chs[0]

numbers[2]

chs[1]

numbers[3]

default!.

成功: 进程退出代码 0.

上面的案例,之所以输出default!.是因为chs[0]和chs[1]都是空值channel,和空值channel通信永远都不会成功。

此示例使用非空值channel进行验证。

//main.go

package main

import (

"fmt"

)

//定义几个变量,其中chs和numbers分别代表通道列表和整数列表

var ch1 chan int = make(chan int, 1) //声明并初始化channel变量

var ch2 chan int = make(chan int, 1) //声明并初始化channel变量

var chs = []chan int{ch1, ch2}

var numbers = []int{1, 2, 3, 4, 5}

func main() {

select {

case getChan(0) <- getNumber(2):

fmt.Println("1th case is selected.")

case getChan(1) <- getNumber(3):

fmt.Println("2th case is selected.")

default:

fmt.Println("default!.")

}

}

func getNumber(i int) int {

fmt.Printf("numbers[%d]\n", i)

return numbers[i]

}

func getChan(i int) chan int {

fmt.Printf("chs[%d]\n", i)

return chs[i]

}

编译运行:

C:/go/bin/go.exe run test4.go [E:/project/go/proj/src/test]

chs[0]

numbers[2]

chs[1]

numbers[3]

1th case is selected.

成功: 进程退出代码 0.

此示例,使用非空值channel进行IO操作,所以可以成功,没有走default分支。

示例4:如果有多个case同时可以运行,go会随机选择一个case执行

//main.go

package main

import (

"fmt"

)

func main() {

chanCap := 5

ch := make(chan int, chanCap) //创建channel,容量为5

for i := 0; i < chanCap; i++ { //通过for循环,向channel里填满数据

select { //通过select随机的向channel里追加数据

case ch <- 1:

case ch <- 2:

case ch <- 3:

}

}

for i := 0; i < chanCap; i++ {

fmt.Printf("%v\n", <-ch)

}

}

编译运行:

C:/go/bin/go.exe run test5.go [E:/project/go/proj/src/test]

成功: 进程退出代码 0.

注意:上面的案例每次运行结果都不一样。

示例5:使用break终止select语句的执行

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

var ch = make(chan int, 1)

ch <- 1

select {

case <-ch:

fmt.Println("This case is selected.")

break //The following statement in this case will not execute.

fmt.Println("After break statement")

default:

fmt.Println("This is the default case.")

}

fmt.Println("After select statement.")

}

编译运行:

C:/go/bin/go.exe run test15.go [E:/project/go/proj/src/test]

This case is selected.

After select statement.

成功: 进程退出代码 0.

关于带缓冲的channel

带缓冲的channel是我们经常作为队列使用的,不带缓冲的一般都是作为信号使用,是阻塞的,带缓冲的在满了之前是非阻塞的,满了也是阻塞性的

创建一个带缓冲区的channel需要一个额外的参数容量来表明缓冲区大小:

ch := make(chan type, capacity)

上面代码中的 capacity 需要大于0,如果等于0的话则是之前学习的无缓冲区channel。

例子

package main

import (

"fmt"

)

func main() {

ch := make(chan string, 2)

ch <- "naveen"

ch <- "paul"

fmt.Println(<- ch)

fmt.Println(<- ch)

}

上面的例子中,我们创建了一个容量为2的channel,所以在写入2个字符串之前的写操作不会被阻塞。

我们再来看一个例子,我们在并发执行的goroutine中进行写操作,然后在main goroutine中读取,这个例子帮助我们更好的理解缓冲区channel。

package main

import (

"fmt"

"time"

)

func write(ch chan int) {

for i := 0; i < 5; i++ {

ch <- i

fmt.Println("successfully wrote", i, "to ch")

}

close(ch)

}

func main() {

ch := make(chan int, 2)

go write(ch)

time.Sleep(2 * time.Second)

for v := range ch {

fmt.Println("read value", v,"from ch")

time.Sleep(2 * time.Second)

}

}

上面的代码,我们创建了一个容量是2的缓冲区channel,并把它作为参数传递给write函数,接下来sleep2秒钟。同时write函数并发的执行,在函数中使用for循环向ch写入0-4。由于容量是2,所以可以立即向channel中写入0和1,然后阻塞等待至少一个值被读取。所以程序会立即输出下面2行:

successfully wrote 0 to ch

successfully wrote 1 to ch

当main函数中sleep2秒后,进入for range循环中开始读取数据,然后继续sleep2秒钟。所以程序接下来会输出:

read value 0 from ch

successfully wrote 2 to ch

如此循环直到channel被关闭为止,程序最终输出结果如下:

successfully wrote 0 to ch

successfully wrote 1 to ch

read value 0 from ch

successfully wrote 2 to ch

read value 1 from ch

successfully wrote 3 to ch

read value 2 from ch

successfully wrote 4 to ch

read value 3 from ch

read value 4 from ch

长度和容量

容量是指一个有缓冲区的channel能够最多同时存储多少数据,这个值在使用make关键字用在创建channel时。而长度则是指当前channel中已经存放了多少个数据。我们看下面的代码:

package main

import (

"fmt"

)

func main() {

ch := make(chan string, 3)

ch <- "naveen"

ch <- "paul"

fmt.Println("capacity is", cap(ch))

fmt.Println("length is", len(ch))

fmt.Println("read value", <-ch)

fmt.Println("new length is", len(ch))

}

上面的代码中我们创建了一个容量为3的channel,然后向里面写入2个字符串,因此现在channel的长度是2。接下来从channel中读取1个字符串,所以现在长度是1。程序输出如下:

capacity is 3

length is 2

read value naveen

new length is 1

有状态的channel

我们正常在使用channel的时候,希望一个全局使用一个channel来分配到对应的goroutine中去,这个时候就需要使用到有状态的channel

正常有状态的channel都是使用map的k来标识,通常使用如下

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

things := make(map[string](chan int))

things["stuff"] = make(chan int, 2)

things["stuff"] <- 2

mything := <-things["stuff"]

fmt.Printf("my thing: %d", mything)

}

吞吐极限

吞吐极限10,000,000(1千万)

异步接受返回结果

针对来一个请求,启动一个groutine来处理,需要拿到返回结果的或者错误结果的。

你需要预先创建一个用于处理返回值的公共管道. 然后定义一个一直在读取该管道的函数, 该函数需要预先以单独的goroutine形式启动.

最后当执行到并发任务时, 每个并发任务得到结果后, 都会将结果通过管道传递到之前预先启动的goroutine中.